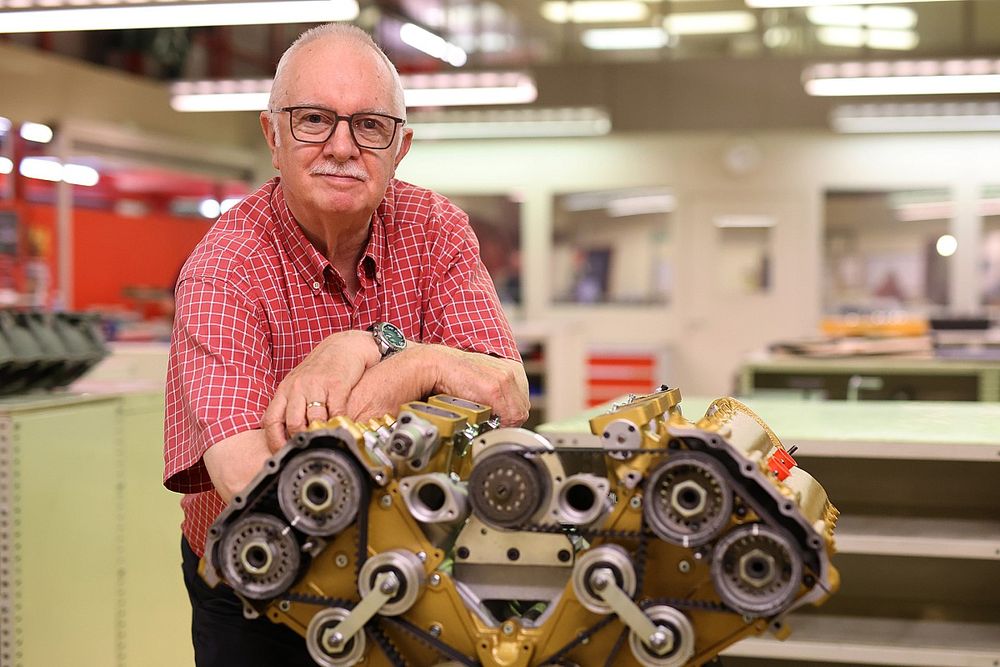

How to be an ace engineer: Engine builder Richard Langford

The boss of engine specialist Langford Performance Engineering opens up on a half century in the industry and working in the historic field

Photo by: JEP / Motorsport Images

Engineering

Our experts' guide on how you can become a better racing driver

After over 50 years of working with racing engines, there are few better qualified than Richard ‘Dick’ Langford when it comes to the art of extracting horsepower.

Having begun his career at Cosworth just as the world-beating DFV was beginning to build its formidable reputation, and serviced much of the Formula 1 grid during the 1970s, he co-founded his own engine-building company in 1980 that became a successful tuner of DFVs in Formula 3000 and supplied several F1 teams.

Today, his Langford Performance Engineering concern focuses on historic road and race engines, and still builds new HB V8 engines alongside its restoration work - having recently completed a Coventry Climax V8 project for a Lotus 25 customer.

Langford leads a “tight-knit bunch” of seven staffers, his longest-serving employee present since 1986 when former Cosworth colleague Alan Peck’s involvement meant the business was known as Langford & Peck. Langford took over when Peck stepped back in 1993 and LPE took its current name.

“Everybody used to call us L&P, so we just kept the initials,” says Langford, whose broad motorsport experience has also encompassed winning the 1997 British Rally Championship with Nissan’s Mark Higgins, and touring cars with Honda.

It’s no coincidence that the company originally founded to service DFVs is located in Wellingborough, just down the road from the Northampton base where Langford and Peck spent a combined 25 years in Cosworth’s engine shop building F1’s most famous power unit. Langford, bitten by the motorsport bug after attending the 1955 British Grand Prix at Aintree, had joined in 1967 after completing an apprenticeship with Ford and became an engine specialist “by chance really”.

Joining Peck, they worked closely for long hours as the ceaseless demand for the powerful and affordable DFVs – that won 155 grands prix across 17 consecutive seasons – meant the technicians manning Cosworth’s engine shop “hadn’t got time to breathe”.

Ubiquity of the Cosworth DFV in Formula 1 during the 1970s meant Langford, Peck and the technicians manning the engine shop were always busy

Photo by: David Phipps

“For a number of years at Cosworth we were really strapped,” he says. “You won’t believe the hours we used to work to make sure the engines were finished. It was exceptional. Everybody did their bit, because we were making history. Lucky we were young…”

Langford describes Cosworth as “one big family” in those days and praises its founders Keith Duckworth and Mike Costin as “excellent bosses”. Moreover, they were “quite supportive in us going on our own,” Langford recalls of L&P’s start.

“It happened at the right time,” he says. “We worked closely together [with Cosworth] for a number of years before [F1] went to major engine manufacturers, which changed everything then.”

"We made that decision very early on that we wanted quality, attention to detail, and customers to be happy. It would have been quite easy to take on lots more work and really fall down on quality and service, then probably lose customers for it" Richard Langford

Their long-standing relationships with DFV customers proved crucial in the early days of L&P as it built and tested engines “that weren’t on the Cosworth development cycle” for F1 squads.

“Alan and I used to run the engine shop at Cosworth, so we used to speak to all of these people on a regular basis because of getting engines ready for the grands prix,” Langford says. “Alan had a very good relationship with Ken [Tyrrell] and he gave us initially a chance to do some DFVs for him, because Cosworth couldn’t handle all of it. That blossomed there, and that’s where it all started.”

During his time at Cosworth, Langford hadn’t been able to attend races. But that changed when L&P became a supplier in the nascent F3000 championship in 1985 and he alternated with Peck in providing on-site customer support.

“We both had our different outlooks to how one was going to approach things,” he says.

The switch from Formula 2 to the new series, so named after the 3000cc engine capacity of the DFV that would form the new series’ backbone, gave L&P its desired foothold onto the international scene as an engine developer.

L&P became suppliers to the Onyx and Madgwick teams in F3000 - with Stefano Modena becoming champion for the former in 1987

Photo by: Motorsport Images

L&P already “knew the DFV inside out” since “it was part of us really,” Langford says, and forged a partnership with Mike Earle’s Onyx Racing team that made it a regular winner with Emanuele Pirro. Against stiff opposition, L&P came close to winning the inaugural title as Pirro finished third – a result he matched in 1986.

Stefano Modena then delivered the title for Onyx and L&P in 1987, when engine management systems were introduced and created an entirely new avenue for exploration, and plenty of blind avenues that were neatly sidestepped.

The partners made a commitment, Langford says, that “we didn’t want to spread ourselves [too thinly]”. Although Robert Synge’s Madgwick team was added to its F3000 customer portfolio for 1987, with Andy Wallace putting in some strong performances following the team’s switch from March to Lola, it was careful about making promises that couldn’t be fulfilled. This ethos also meant L&P kept a deliberately small machine shop to focus on upholding standards “as good as Cosworth’s machine shop”.

“We made that decision very early on that we wanted quality, attention to detail, and customers to be happy,” Langford explains. “We were a young company building our reputation and staff and training people. It would have been quite easy to take on lots more work and really fall down on quality and service, then probably lose customers for it. We made decisions that success was initially for us, more [important] than profit.

“We did have other people ring up and ask us, but we committed ourselves at the beginning of the season, and that’s what we carried on.”

L&P’s relationship with Onyx – which had toiled with an uncompetitive F3000 March in 1988 – continued when Earle’s outfit stepped up to F1 for 1989. The company also counted Tyrrell, Ligier and Coloni among its customers that year, as its operations expanded to include F1 DFR engines – a highly-developed derivative of the DFV. L&P continued to service Tyrrell, Ligier and Coloni in 1990, alongside its ongoing commitment to Madgwick in F3000.

Its last win in the International Series came at Silverstone in 1989 as Mugen’s arrival with a bespoke engine built for the formula – rather than a DFV pegged back to 9000rpm – moved the goalposts, but L&P DFVs still won four British F3000/British F2 titles with Madgwick courtesy of Pedro Chaves (1990), posthumous champion Paul Warwick in 1991, Philippe Adams in 1993 and Jose Luis di Palma in 1994.

Langford went to events in a supporting capacity during L&P's peak, but most enjoyed organising spares supplies and servicing schedules

Photo by: JEP / Motorsport Images

L&P’s final involvement in International F3000 was in 1992 with the Apomatox Lola outfit, taking a Magny-Cours podium with Olivier Panis, as its F1 commitments intensified.

Cosworth had built an all-new V8 engine, the HB, that was initially used by Benetton in 1989 before being made available to customers for 1991. L&P was contracted by Cosworth “to do all of the customer HB work” which initially meant supporting F1 newcomer Jordan – and prodigious newcomer Michael Schumacher – then in 1992 Lotus and Fondmetal. Minardi joined the fold for 1993, with Footwork, Larrousse and Simtek following suit in 1994.

F1 “was more demanding” than F3000, requiring more preparation to ensure there were enough spares and that schedules for part servicing were set, as well as interacting with design teams to make sure all the requirements for the bespoke installations were met. This, Langford says, was an aspect he particularly enjoyed as he took turns alternating with Peck in going to race meetings, as they did in F3000, and managing a staff of 28 at the height of its F1 involvement.

LPE has two dynamometers at Wellingborough – including a high-speed dyno that can run to 20,000rpm for testing V10 engines – and works closely with external machine shops and reverse-engineering specialists, having “formed relationships with [them] for a number of years that cater for all that we do”

“I most enjoyed the preparation and the ongoing development requirements to make sure the package we were providing was the best we could give at the time,” he says. “There was planning for spares, engines, when engines would be returned and how quickly they had to be turned around – you couldn’t ask for a grand prix to be postponed because you hadn’t got an engine ready.

“There was a lot more planning and getting here, there and everywhere, travelling all over the world, it was a different ball-game totally.”

LPE’s most recent contemporary F1 involvement was with the 3.0-litre VJ-M V10 used by Minardi in 2001, the second time Fernando Alonso had used its products after he’d won the 1999 Euro Open by Nissan series with four-cylinder engines prepared in Wellingborough.

Langford’s links with Minardi remain today as LPE still services the engines for Stoddart’s fleet of two-seater F1 cars based on the 1998 Tyrrell and, having acquired the rights to the HB from Cosworth, is a one-stop shop for 3.5-litre era F1 machines.

PLUS: Autosport discovers F1’s true brutality in the two-seater

There was also a British Touring Car Championship programme for LPE as Langford linked up once more with Earle, now under the Arena Motorsport banner, with a Honda Civic Type-R that Tom Chilton took to four race wins in 2005.

L&P built the customer HB Cosworth engines that powered Schumacher's Jordan 191 in 1991 - Langford now owns the licence to this engine

Photo by: Ercole Colombo

“After that we concentrated on projects in historics,” he says of a fruitful period that has encompassed Group C with Jaguar XJR14, historic F1 and hillclimbing. “We worked on DFVs, the HB, we did FVAs, FVCs, twin-cams, we’ve just recently done a Coventry Climax V8 that’s started us off in something else.

“We do restoration projects too, so we did a lot of work for Aston Martin on DB restoration engines and Jaguar on their E-Type reborn programme, so it keeps us busy.”

LPE has two dynamometers at Wellingborough – including a high-speed dyno that can run to 20,000rpm for testing V10 engines – and works closely with external machine shops and reverse-engineering specialists, having “formed relationships with [them] for a number of years that cater for all that we do.” Langford relishes the variety, but also the satisfaction that comes from involvement in restoring engines akin to “something being buried in the bottom of a lake for 20 years” back to peak working order.

“When you’re given the task of restoring that and it becomes then a pristine engine, it’s a real challenge but one that brings high reward,” he says. “We’ve just done one recently for Jaguar Land Rover Classics, and that was a 1965 E-Type that was absolutely derelict. The engine looked like it had been through an atomic war. And that car then drove in the Queen's Platinum Jubilee Pageant, it’s pristine!”

Langford’s passion for precision engineering is clearly undimmed, and a lifetime of experience means LPE customers are in the most capable of hands.

“I always knew what I wanted to do was be involved in motorsport,” he says. “So I was lucky.”

Today Langford remains busy working with customers in the historic sphere, including complete restorations

Photo by: JEP / Motorsport Images

Advice for engineers from Richard Langford

· It was instilled in me that you need to really look at components. When you come up against problems, then you need to really look at it and understood what’s going on so you can form an opinion and an analysis of the problem. Look and understand. Don’t look at it, but look at it.

· Really think about your decisions and don’t make a rash one, but do make a decision. Don’t waffle around, make a decision. That was crucial really because it could have big consequences in cost if you made the wrong one, or whether an engine would get delivered on time.

· Forward plan, cater for eventualities that you probably haven’t thought of. Then go back and look again. Even from the F3000 days, planning and making sure the parts were there to service engines was key.

Attention to detail has always been an important aspect of Langford's repertoire

Photo by: JEP / Motorsport Images

Be part of the Autosport community

Join the conversationShare Or Save This Story

Subscribe and access Autosport.com with your ad-blocker.

From Formula 1 to MotoGP we report straight from the paddock because we love our sport, just like you. In order to keep delivering our expert journalism, our website uses advertising. Still, we want to give you the opportunity to enjoy an ad-free and tracker-free website and to continue using your adblocker.

Top Comments