F1 rule changes: what’s new in 2022 and how have rules affected racing?

Formula 1 has introduced sweeping new regulations for 2022, aimed at improving the racing. But how successful have previous F1 rule changes been? Autosport picks out the hits and misses.

Photo by: McLaren

Anyone who has taken a glance at the new batch of Formula 1 contenders can see that things will be different in 2022.

The regulation changes are regarded as the biggest shift in F1 since 1983, but the aims of the new rules are relatively simple. A move away from complicated ‘overbody’ aerodynamic devices and the reintroduction of ground-effects (the creation of downforce using the car’s floor) are meant to reduce the impact of ‘dirty’ air.

PLUS: Unpacking the technical changes behind F1 2022's rules shakeup

The problem of ‘dirty’ air has been a growing one since the 1980s. Essentially, the disturbance created by the car ahead means any car following has less air going over its wings and other downforce-generating surfaces. The following machine thus has less grip and cannot corner as quickly, even if it is faster. Overtaking has thus become more difficult.

As aerodynamics have become more sophisticated the problem has become worse, more than offsetting the gain of a slipstream on straights. The Drag Reduction System – which allows a chasing car to open a flap in the rear wing to reduce drag and boost straightline speed when within one second of the car ahead – is really an attempt to plaster over the crack.

Ground-effects cars are less affected by dirty air and the new rules have also been designed to fling the disturbance over following cars rather than at it. The result should be that cars can follow each other more closely.

The restrictive regulations, combined with the cost-cap and windtunnel limitations, are also designed to enable more teams to run at the front. More winners and closer racing are the hoped-for results of the new era.

PLUS: Karun Chandhok's 10 big questions facing F1 2022

But how successful have previous F1 rule changes been? Can we expect the new regulations, which are the result of greater research and study than any previous ruleset, to improve the spectacle?

We’ve decided to take a look back at the biggest rule changes in F1 history and decide whether they were a hit, miss or maybe.

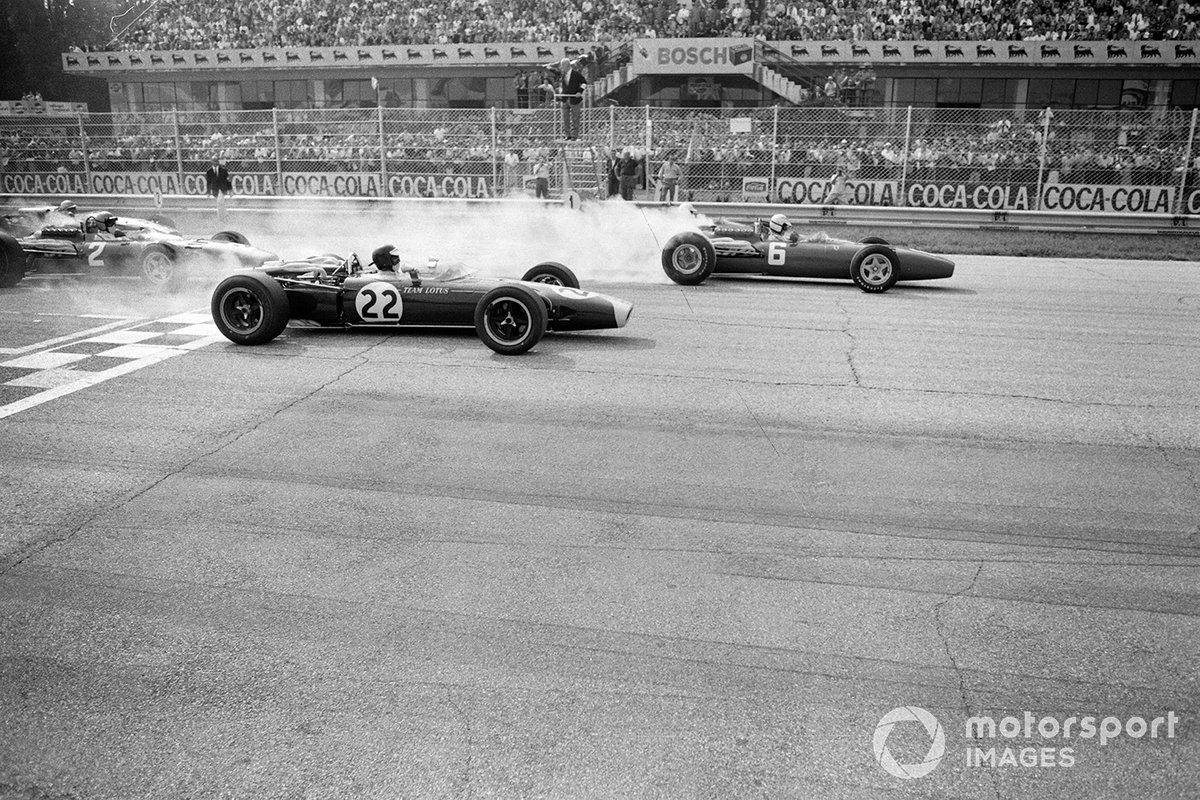

New rules for 2022 reverse the abolition of ground effect that was brought into effect in 1983

Photo by: Motorsport Images

Assessing whether targets are met is, of course, the obvious way to evaluate any rule change. But F1 has a history of problems with unintended consequences.

For example, the introduction of turbo-hybrids for 2014 did make F1 more relevant to the road industry in environmentally conscious times, but increased powerplant expense and spread out the field, with Mercedes dominating for the period’s first three seasons. Some also criticised the sound of the engines compared to the V10s and V8s that preceded them.

Other factors, not directly related to the rules, such as the drivers involved, also have an impact on how a particular F1 era is remembered. While muddying the waters of this debate, they cannot be entirely disregarded.

So, here’s our assessment of F1’s most significant regulation eras, including both a look at how they met their targets and their overall impact and popularity.

1952 – Formula 2 regulations

Alberto Ascari's Ferrari leads the pack at the start of the 1952 Belgian Grand Prix

Photo by: Michael Tee / Motorsport Images

With Alfa Romeo finally defeated and withdrawing from the sport, BRM having failed to get its act together and few others with a serious Formula 1 programme capable of challenging Ferrari, the decision was made to run the world championship to F2 regulations for 1952.

The unsupercharged two-litre formula already existed, was relatively cost-effective and did succeed in making sure grid numbers were strong. But it did nothing to stop domination by Ferrari, which won every single world championship grand prix (excluding the Indianapolis 500, which then counted for points).

PLUS: Ferrari’s first world-championship winning machine

It was a similar story the following year, only a late incident helping Juan Manuel Fangio take victory for Maserati in the Italian GP finale and preventing another Ferrari whitewash.

The cars were less spectacular than their 1.5-litre supercharged and 4.5-litre unsupercharged predecessors, and their 2.5-litre unsupercharged successors. Given the pace of the BRM and Ferrari-based Thin Wall Special in Formula Libre races, Ferrari might have had more meaningful opposition without the rule change.

VERDICT: MISS

1954 – The first ‘real’ F1

The 1954 arrival of the Maserati 250F and Mercedes W196 - driven here by Stirling Moss and Juan Manuel Fangio at the Spanish GP - heralded the beginning of 'real' F1

Photo by: Motorsport Images

The original F1, initially known as Formula A, was based on the pre-Second World War Voiturette category. So the first ‘proper’ F1 arrived in 1954 for 2.5-litre unsupercharged machines.

Mercedes returned to the sport with the W196, which would become legendary, Maserati introduced its iconic 250F and Lancia (eventually) arrived with its superb D50. Along with the Vanwall, which won the inaugural F1 constructors’ title in 1958, these are regarded as some of the finest cars in GP history.

PLUS: How the first F1 Mercedes laid the path of greatness

F1 also became closer during this rules era and there was plenty of innovation. Disc brakes became the norm and, by the final year of the 2.5-litre regulations, most of the leading teams were switching to rear-engined designs.

VERDICT: HIT

1961 – The 1500cc era

Ferrari dominated 1961, but at the Nurburgring that year Stirling Moss took a remarkable victory for Lotus

Photo by: David Phipps

Judged by how the decision to switch to less-powerful 1.5-litre cars was initially received, particularly by the British teams, this would be regarded as a failure. But those early feelings were wrong.

Although Ferrari initially stole a march, the field soon closed up again. While Jim Clark and Lotus dominated in 1963 and 1965, the 1962 and 1964 title fights went down to dramatic finales and there was some great racing.

Within two to three years, lap times had also surpassed those of the previous era, helped by developments such as the introduction of monocoque chassis.

PLUS: F1’s great landmarks – Lotus 25

The rise of big-banger sportscars meant changes were required to restore F1’s status as the world’s fastest category, but very few would regard the 1961-65 era as a failure.

VERDICT: HIT

1966 – F1’s return to power

The arrival of three-litre rules for 1966 spawned the DFV that made F1 more competitive than ever

Photo by: Rainer W. Schlegelmilch / Motorsport Images

It’s hard to argue that an engine formula that lasts for more than two decades is anything other than a success. The first season of the three-litre regulations produced something of a hotchpotch as many teams struggled to find suitable powerplants. But the arrival of the Ford-backed Cosworth DFV in the Lotus 49 moved the competitive goalposts and, once it became available to other teams, helped make F1 closer and arguably more accessible than ever before.

Some teams, most notably BRM and Ferrari, prevented F1 from completely becoming a grown-up version of Formula Ford but, where the engine variety was perhaps lacking, the extent of chassis and aero innovation meant the cars were still distinctly different.

PLUS: The greatest engine in F1 history

Wings, sponsorship, slicks and ground-effects all arrived during the late 1960s and 1970s. In hindsight, it was the era that set up some of the issues motorsport continues to battle – technical innovation becoming expensive and pushing F1 into realms that threatened the sport, such as ‘dirty’ air from wings and the rise of excessive budgets – but at the time it was exciting. Things changed quickly, there were multiple different winners and the advantage swung back and forth regularly.

It’s perhaps not a surprise that the 1974-82 part of this era was voted the best period for F1 by Autosport magazine readers in 2018-19.

VERDICT: HIT

1983 – Flat bottoms replace ground-effects

Brabham took the 1983 title with Nelson Piquet, but at Brands Hatch his team-mate Riccardo Patrese led the early stages

Photo by: Motorsport Images

One of the most significant rule changes came late, ground-effects essentially being outlawed in the closing months of 1982. Several teams, most notably Brabham, had to bin well-developed designs and start again.

PLUS: When BMW added F1 'rocket fuel' to ignite Brabham's 1983 title push

Flat bottoms were introduced to reduce cornering speeds following several serious crashes, while the stiff suspension required to optimise the suction generated by ground-effects could make the cars unpleasant to drive.

The turbo war not only soon pushed lap times faster than ever, it also spread out the field, the gaps between the haves and have-nots being enormous at times as McLaren and Williams largely set the pace.

And yet the cars were spectacular – the most powerful in F1 history at the height of the turbos before pop-off valves curtailed their incredible outputs – there was some fantastic races and the era included such great names as Nigel Mansell, Nelson Piquet, Alain Prost and Ayrton Senna.

Supremo Bernie Ecclestone’s push to make the championship more professional and to increase TV coverage also boosted F1’s popularity during the 1980s.

VERDICT: HIT

1989 – Away with turbos

McLaren remained the team to beat in 1989, with Senna and Prost's battle for the title only decided in the latter's favour after a controversial last round clash at Suzuka

Photo by: Motorsport Images

Turbos were banned for 1989, replaced by 3.5-litre naturally aspirated engines. While McLaren retained its place at the top of F1, the competitiveness at the front of the field initially improved and there were record-breaking entry levels. Not all the teams were serious outfits, but it’s probably fair to say F1 was more accessible then than it has been so far in the 21st Century.

The arrival of various electronic aids – notably semi-automatic gearboxes, traction control and active suspension – spread the field out in 1992-93, with Williams moving ahead with its technology.

There were, however, still some legendary races during the period and the cars were among the greatest in F1, both in terms of the challenge they posed to drivers and their aesthetic appeal.

Top 10: Ranking the best-looking F1 cars

As well as Senna, Mansell and Prost battling it out, the era also included the arrival of Mika Hakkinen and Michael Schumacher, though the unsatisfactory conclusions to the 1989 and 1990 title fights must be regarded as a negative.

VERDICT: HIT

1994 – Banning of the gizmos

The expected duel between Schumacher and Senna in 1994 sadly didn't last due to the latter's death at Imola

Photo by: Motorsport Images

No rule change in F1 history closed up the field like the banning of electronic aids, including traction control and active suspension. The big teams, in particular Williams, had moved clear of the field with such innovations during the early 1990s and lost much of their advantage.

Refuelling was reintroduced, making tyre preservation less of a factor, but it also increased the risk of fire, as famously demonstrated by Benetton and Jos Verstappen at the 1994 German GP.

The championship contest between Schumacher and Damon Hill was the closest for many seasons, but the year was also tumultuous. The deaths of Roland Ratzenberger and Senna at Imola rocked motorsport and led to many changes, including the emasculation of several circuits, while there was much controversy surrounding Benetton, from its alleged used of traction control to the clash between Schumacher and Hill that decided the title in Adelaide.

How many of those negatives could be attributed to the 1994 rule changes is open to debate, though they are hard to ignore, and many drivers reported that the cars were more difficult following the banning of the gizmos.

The next few years were also relatively successful, with Schumacher (first at Benetton, then at Ferrari) battling Williams for supremacy.

VERDICT: MAYBE

1998 – Narrow cars and grooved tyres

Hakkinen and Schumacher do battle in the 1998 Argentine Grand Prix, a snapshot of their season-long duel for the title ultimately decided in the McLaren's favour

Photo by: Sutton Images

Reducing speeds and helping overtaking were the main targets of the 1998 regulations. The width of the cars was reduced by 200mm and grooved dry tyres replaced slicks.

Combined with other factors – namely, trouble at Williams and Adrian Newey heading to McLaren – the rules did provide a change in the competitive order. Reducing the contact patch of the tyre and, therefore the amount of mechanical grip (not influenced by dirty air), didn’t aid overtaking. And, as ever, it took teams very little time to recover the lost performance, so it’s questionable that the ruleset’s aims were achieved.

On the other hand, there were still strengths inherited from the previous era. The three-litre engines (brought down from 3.5 litres in 1995), which had to be V10s from 2000, are widely regarded as among the best in F1 history.

Refuelling also made many of the races a series of sprints, probably the closest F1 has ever got to flat-out competition, with little consideration of tyre wear, fuel saving etc required. While that is now considered a positive, it also meant many races were dull affairs, with the order being established early on and changes of position often only happening during the pitstop phases.

Thanks to policing issues, traction control officially returned during this period, but was banned again for 2008 as standard ECUs arrived. This was also the era in which F1 said good-bye to three-litre V10s, replacing them with 2.4-litre V8s…

Much of the period was dominated by Schumacher and Ferrari, though it also encompassed the rise of Fernando Alonso and Renault, the arrivals talents including Kimi Raikkonen, Lewis Hamilton and Sebastian Vettel, and finished with the tight Ferrari-McLaren contests of 2007-08.

VERDICT: MAYBE

2009 – Another aero clampdown

Former Honda team, under Brawn guise, became the pace-setter in 2009 as Button took his sole F1 title

Photo by: Steve Etherington / Motorsport Images

The return of slick tyres and ‘cleaner’ aerodynamics, with many of the flicks and winglets removed, should have made the 2009 regulations a clear win. They brought a change to the competitive order, with Brawn and Jenson Button taking popular titles and Red Bull becoming a frontrunning force for the first time.

The 2009 season was also the closest yet in terms of the raw pace gap between the front and back of the field. Thanks partly to Pirelli’s deliberately fragile rubber, there was the remarkable run of seven different winners in the first seven races of 2012.

PLUS: When was F1 closest?

And yet, many of the cars during this ruleset were ugly, and the aero changes did little to help the problem of overtaking. That much was tacitly accepted by the arrival of DRS in 2011, a move F1 has yet to do away with.

Vettel and Red Bull also ended up dominating much of the period, taking four consecutive titles and ending the era with nine straight victories.

Verdict: MISS

2014 – F1 turns to turbo hybrids

Mercedes became F1's dominant team as the turbo hybrid era began in 2014

Photo by: Steven Tee / Motorsport Images

F1 was rather slow to respond properly to environmental concerns, but turbo-hybrid power arrived for 2014. F1 perhaps didn’t shout about the efficiency of the new engines as much as it should and, instead, much of the talk was of them being too quiet and expensive.

In reality, the noise issue was a red herring and the change needed to happen, but the costs and complexity of the engines did spread out the field. Mercedes grabbed an advantage that was only eroded (though not overcome) when the wider, faster and better-looking cars arrived for 2017.

While overtaking issues remained, the field did close up as the era progressed, culminating in Red Bull’s Max Verstappen toppling Hamilton in 2021. That year also had one of the smallest raw speed gaps between the top team and fifth-fastest squad in the history of the championship.

Liberty Media took over the running of F1 and made changes that helped increase the popularity of grand prix racing, though that was offset somewhat by race stewarding issues that resulted in the FIA making changes for 2022.

Nevertheless, some surprisingly good races and the rise of talents such as Verstappen, Charles Leclerc, Lando Norris and George Russell mean that, despite the unpopular start, the era has to be regarded as a success.

It’s also worth noting that, given efforts to slow F1 down, the cars of this period – most notably the Mercedes W12 of 2020 – are likely to remain the fastest in the championship’s history for some time.

PLUS: The Hamilton record underlining F1’s eternal struggle

VERDICT: HIT

As in 2021, Mercedes and Red Bull led the way as the turbo hybrid era began, although Ricciardo was subsequently disqualified from his second place in Melbourne 2014

Photo by: Steve Etherington / Motorsport Images

Be part of the Autosport community

Join the conversationShare Or Save This Story

Subscribe and access Autosport.com with your ad-blocker.

From Formula 1 to MotoGP we report straight from the paddock because we love our sport, just like you. In order to keep delivering our expert journalism, our website uses advertising. Still, we want to give you the opportunity to enjoy an ad-free and tracker-free website and to continue using your adblocker.

Top Comments